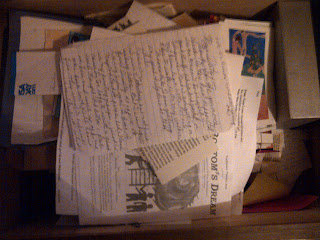

On late Saturday, about 10:30 p.m., my 88-year-old mother called to me from her bedroom as I was getting ready for bed. She was sitting beside a dresser and pointing to an open drawer, stuffed with letters and cards from all sorts of people -- her older sister, some nieces, her grandchildren. The correspondence went back 10, 20 years. "Should I get rid of some of these?" she was asking me.

On late Saturday, about 10:30 p.m., my 88-year-old mother called to me from her bedroom as I was getting ready for bed. She was sitting beside a dresser and pointing to an open drawer, stuffed with letters and cards from all sorts of people -- her older sister, some nieces, her grandchildren. The correspondence went back 10, 20 years. "Should I get rid of some of these?" she was asking me."Oh no," I said, the writer/journalist/investigative reporter in me thinking, you don't throw away people's letters. Aren't they a part of one's history? Other peoples' memories?

My mother and I sometimes have different ideas about things you keep and things you throw away. She has always liked to keep things tidy, whether it's the spice rack or the carefully folded -- as if ironed -- leftover plastic bags from Safeway. She doesn't have a problem throwing things out that she deems not useful, things that take up space. Very few of my childhood notebooks or private art projects are saved anywhere -- ones I can remember vividly working on quietly in my room. I wish I had made more of an effort to save them myself because these worlds meant a lot to me at the time. I wonder now, if I could look at them, maybe I could uncover a new understanding of the choices I've made in life, the roads I have taken that have landed me in the place I am now.

Meanwhile, my mother keeps all her piano books from childhood, her vinyl records of classical music records, and my father's Navy uniforms. She has kept his last pair of glasses, and carefully arranged photo albums of each of us kids. Of the records, she has recently been playing what was once a semi-controversial 1962 comedy album, "The First Family" -- a satire about life inside the JFK White House. Yes, the JFK years were in some ways the Camelot years for my mother. They coincided with my father becoming principal for the first time of a high school, Del Valle High, near the Rossmoor retirement community. The school was state of the art at the time and staffed by young, enthusiastic teachers who became my parents lifelong friends. Some of them are now dead.

Aside from our differing views of mementos that should be saved, my immediate thought at my mother's sudden request Saturday was how odd it was for her to be approaching me about a drawerful of letters at this time at night. It's something she'd bring up on a weekday morning, or earlier in the evening. But that Saturday night, her face was pointed with some strange new urgency, as if she knew something was going to change soon.

Early the next morning at about 1 a.m. Sunday, my husband heard her call out both his name and other names he didn't quite recognize. She had fallen in her room, in the dark, as she was getting out of bed and trying to make her way to the bathroom. We found her in her nightgown and robe, sitting on the floor, looking slightly confused. And then she showed us she was in a lot of pain when she moved her arms one way or another in attempt to hoist herself up from the floor. She fell back down. The pain was in her chest, and it hurt her to take a deep breath. We urged her to keep still, and called 911. We wrapped her in a blanket. She was vague about what happened in the dark, what piece of furniture she had fallen against. Maybe she had hit her head on the way down. She wasn't sure how long she had been sitting there, and maybe she had spent a few minutes crawling to the center of the room.

The ambulance came, with the paramedics, who were able, on that clear, cold Saturday night, with temperatures hovering in the 30s, to help her walk out of the house and into the ambulance. My husband told me to stay home. He would meet her at the emergency room. Selfish me, I was glad to be spared an overnight ER session. The excuse was that I should be home to greet our son in the morning, but I also thought, I'm sending my husband, whose own medical condition -- schizoaffective disorder -- means he should be getting a good nights' sleep. Instead he's going off to the ER land of artificial air and uncomfortable waiting room chairs. At least, I thought, he's got a good relationship with my mother, and he's good in these kinds of medical crises. I recently said to him, after writing a story for the UCSF School of Nursing magazine, about the growing number of men in nursing, that he would have made a good nurse.

As I've mentioned on my Facebook page, my mother, after X-rays and a CT Scan of both her chest, torso and head, was found to have two fractured ribs and a fractured sternum. Not much you can do about these in the way of surgery or wrapping them up. In fact, the course of treatment was to get my mother up and moving as much as possible, without letting her move in ways that would re-injure her broken bones. They gave her pain meds, and got her up out of bed, to walk around using a walker.

The doctor was very adamant -- that from now on she needs to use a walker. This order somehow tells us we have entered a new phase in our lives and in her fragility. Her balance has been a bit off for quite some time. There is weakness in her feet and legs, though she presumably can start counteracting that weakness with exercises she's learning in rehab for the next few days at a skilled nursing facility, which just so happens to be located off Tice Valley Boulevard, on the property that once housed the long-shuttered Del Valle High School.

On the Sunday and Monday after the fall, she was kind of out of it, disoriented, forgetful of people she had just talked to a few minutes earlier. Her speech was slurred. No doubt, the pain meds were contributing to her disorientation. But then I worried: Had she suffered a stroke? One of her doctors mentioned that her chart noted an earlier visit -- years earlier -- where it was suspected she had suffered what they call a trans ischemic attack, a mini-stroke. The doctor speculated that she had suffered one just before her fall early Sunday morning. That could explain her confusion about her fall.

I started to wonder if the attack had started to happened hours earlier, after she returned at 7 p.m. Saturday from a party of old friends -- teachers and administrators my father used to work with at Del Valle High Scool. She walked into the house with a dish left over from the party and put it in the fridge. My husband, son, and I was were sitting having dinner, a bit tired from an all-day wrestling tournament. She sat down on the sofa near us. Usually, when she comes home from one of her parties, she regales us with old gossip, tales of people she saw, or about people who couldn't make it because they are in the hospital. Or people who are dead. The names passing from her lips are names of people I knew growing up.

She didn't say much as we ate dinner. She actually seemed out of breath, which is unusual for her. She's in pretty good shape, and never had any problem climbing the front steps to our house. But she was out of breath and quiet, and then my son overheard her mutter something, like "Merry Christmas, Bill."

Bill is my father's name. My mother, who believes in her version of heaven, is not afraid of dying, because she believes she will rejoin her husband of nearly 52 years somewhere in the afterlife.

My husband eventually heard from nursing staff at both the hospital and the nursing home that her confusion on Sunday and Monday is normal for older people who have been in a fall and who are in pain. It usually goes away after a few days. So, maybe she had not suffered any kind of stroke after all, but I'm still not sure what was going on Saturday night.

Yesterday, I gathered up some of the letters from the drawer she was worried about to take to the nursing home. She was sitting upright in a chair, feeling chatty about her day, her two rehab sessions, feeling fairly strong and confident -- and to the chagrin of us and her health care workers -- reluctant to use her walker. Yes, the confusion was gone.

I handed her the envelope of letters and told her it would be nice to save them, and pointed out, for example, a long letter from a favorite niece dated 1998. There was probably lots of important information about the niece's life in that letter.

My mother appreciated getting the letters, and I told her I would remove them from the drawer, and put them in a box, to free up space in the dresser. And then, with the box, she could take her time organizing them. My mother worked as a library assistant for the Contra Costa County Library system for some 20 years, so she loves the task of organizing, sorting and labeling.

"Do you think I should organize my date or name?" she asked.

"Name," I suggested. She nodded and agreed.

1 comment:

My thoughts are with you, I'm at an early stage of this part of my mothers life and I am rather afraid of the trials to come.

Post a Comment